Public policy, while rooted in good intentions, finds its true test in real-world application. The National Human Rights Strategy for Disabled People 2025-2030 represents a bold, whole-of-government commitment to a more equitable and inclusive Ireland. This strategy is a powerful step forward, and its success hinges on the ability to transform its ambitious goals into tangible, seamless, and dignified daily experiences for every citizen.

This is where User Experience (UX) design becomes a vital partner. Applying a human-centred UX lens will help ensure the strategy's promises are not only documented but are truly realised, hopefully making a profound and positive impact on the lives of disabled people.

Within the five pillars in the strategy framework, Pillar 5: Transport and Mobility presents a particularly critical design challenge and one that we at Marino are very familiar with. The strategy's commitments to ‘Seamless and accessible journeys in urban and rural areas’ and ‘Personal Mobility’ are, at their core, mandates for a better user experience.

These aren't just about building ramps or adding accessible buttons; they are about designing a complete, end-to-end journey. From the moment a user checks an app for real-time information to the final steps from the bus stop to their destination, the experience must be cohesive. A broken tactile paving, an inaccessible bus stop, or a confusing digital interface, can break the entire journey and undermine a user's independence.

By focusing on personal mobility choices, the strategy also acknowledges a key UX principle, giving users control and a sense of empowerment. Empowering individuals through tools and infrastructure to choose how they move through the world, rather than being dictated by a system full of barriers.

To bridge the policy to practice gap, a fundamental shift in perspective is required. The UX lens recasts the citizen as a user, who must navigate and interact with a complex service ecosystem comprised of government agencies, public infrastructure, and digital platforms. The core principles of UX provide a systematic framework for ensuring this strategy's success, guiding the process from empathetic research to iterative, data-driven delivery.

In this context, it’s crucial to understand the full spectrum of human ability through what is often called the persona spectrum, a framework famously defined by Microsoft's Inclusive Design methodology.

This framework illustrates how a permanent disability (e.g. being a wheelchair user) has temporary and situational equivalents that affect us all. A person with a permanent mobility impairment might face the same challenges as a delivery driver with a temporary leg injury or a parent navigating a train station with a buggy.

Designing for one user, therefore, creates a ripple effect of benefits for countless others. It reminds us that at some point in our lives, we all experience the world with a temporary or situational impairment. By designing for the edge cases, we create solutions that improve the lives of everyone.

The strategy’s co-creation with Disabled Persons' Organisations (DPOs) is a foundational example of a user-centred approach. However, for true success, this must evolve into a continuous, embedded practice. This requires ongoing qualitative research through interviews and journey mapping, coupled with quantitative data analysis. To move beyond consultation to a real and profound understanding of users' needs, pain points, and aspirations, capturing not just what happens but how it feels.

Applying principles like Universal Design and accessible design to build the physical and digital solutions outlined in the strategy. This applies to both the tangible and intangible. The policy's commitment to Transport and Mobility, for example, requires the design of physical infrastructure, from level-access bus stops and tactile paving to clear, intuitive signage, as a user interface that is usable for all.

Concurrently, it demands the development of digital services and transport apps that are fundamentally accessible. This includes compatibility with screen readers, logical keyboard navigation, and the use of clear, unambiguous language to remove digital barriers and foster independence.

Design led service delivery through the existing government, ‘Action Plan for Designing Better Public Services’ laid the foundation for a design approach in Government. In this plan they call out, ‘Design tools, training and knowledge exchange resources will be provided to Public Servants to ensure opportunities to contribute individual talents and perspectives to service design and delivery are realised’.

This design-led approach to public services represents a transformation in service development and delivery which involves putting the needs of service-users first. Similarly we take a ‘whole-of-journey’ approach in our UX projects, applying Universal Design principles ensuring that our digital services, including transport apps are accessible and understood by all.

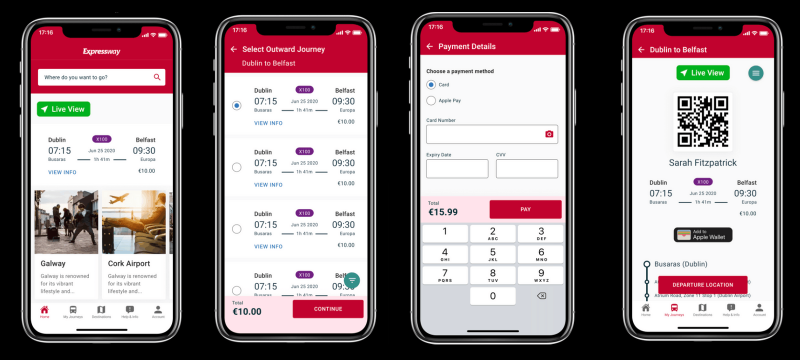

One example is when we partnered with one of Ireland's leading transport services providers, Expressway to design and plan the development of their digital and on-boarding experience.

Through comprehensive user research, we identified current pain points and we used ideation to turn these into opportunities that would not only improve the customer experience but also meet their business goals and drive revenue. During the project, we were asked to look at ways the ticket vending machines could engage customers more clearly and concisely while still meeting business goals.

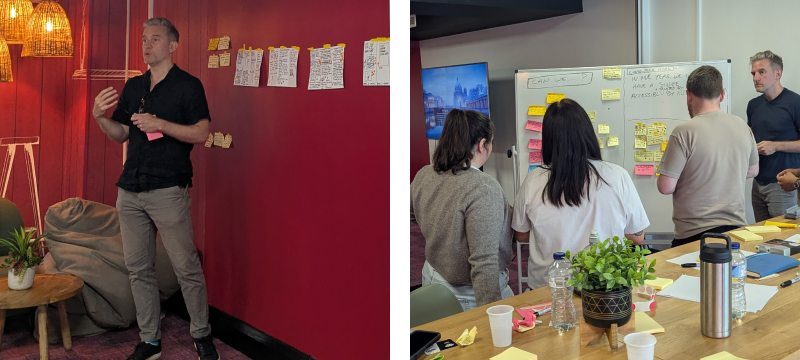

Another way in which we can take a specific commitment from Pillar 5 (like improving access to bus stops) and turn it into a concrete, testable solution in a matter of days is through design sprints. Think of a design sprint as a fast-track to clarity. In just five days, a dedicated team can take a major design challenge, develop a high-impact solution, and test it with real users, allowing for rapid validation and a clearer path forward without months of debate.

It forces a cross-functional team (policymakers, designers, engineers, and most importantly, disabled users) to move past discussion and into tangible action. A sprint allows for the creation of a low-fidelity prototype, perhaps a mobile app mock-up, that can be tested immediately with real users. This rapid feedback loop is crucial for validating ideas and avoiding costly mistakes before they are fully implemented.

A successful policy is not a static document but a living, evolving system. Its effectiveness must be continuously tested, measured, and refined. The strategy’s Programme Plans of Action, on a two-yearly basis, provide an ideal mechanism for this. These plans should function as iterative cycles, where commitments are delivered and their impact is rigorously measured using user feedback and performance indicators.

This iterative loop ensures the policy remains flexible and responsive to real-world outcomes, moving beyond a checkbox exercise toward genuine accountability. Progress not perfection.

The National Human Rights Strategy for Disabled People possesses a transformative potential. By integrating UX principles, empathising with users, designing inclusively, and iterating based on evidence, we can bridge the gap between policy and practice. The true impact of this strategy will not be found in government reports or press releases. It will be measured in the daily lives of disabled people: in our freedom to move with dignity, participate fully, and the seamlessness of all of our journeys through Irish society.

We’re ready to start the conversation however best suits you - on the phone at

+353 (0)1 833 7392 or by email